Coffin Birth: A Rare Postmortem Phenomenon

We don’t know her name, or how she died. Despite this, a medieval mother unearthed in Imola, Italy, was able to give us some fascinating information on life and pregnancy in ancient times.

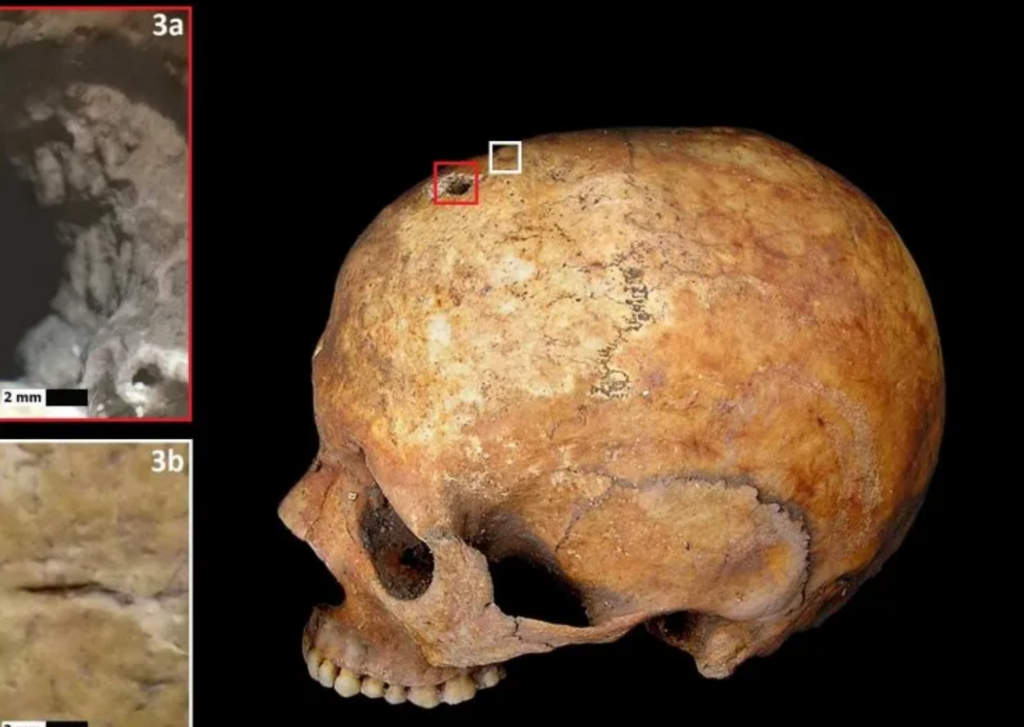

Her bones tell a tragic story of a young life and a pregnancy cut short. The skeleton of the woman was found with a second skeleton, the remains of a fetus, between her legs. There was also a coin-sized hole in her skull.

The minuscule bones were that of her unborn child, expelled from her body after her death. This is due to a gruesome phenomenon known as coffin birth. The skull hole is the result of a medieval medical procedure called trepanation.

Trepanation is interesting in its own right, but today, we’ll be focusing on coffin birth and the sad circumstances that can lead to this post-mortem event.

Coffin Birth, or Postmortem Fetal Extrusion

Despite how it presents itself, the term coffin birth might be a misnomer for what truly happens during postmortem fetal extrusion. Coffin birth is not truly birth in the most technical sense. Instead, it results from the build-up of gasses within the abdomen of the deceased mother. It forces the uterus, and also the fetus if one is present, from the body.

After death, a body will begin to decompose, aided by bacteria in the abdominal cavity. These bacteria are naturally occurring. As they work to decompose the body, the by-product of said decomposition is gas. Meanwhile, soft tissues, organs, and other parts of the body are softening and putrefying.

If the deceased happens to be a pregnant mother, this buildup of gasses causes extreme pressure to be put on the uterus and it can be forced downwards through the body. In rare cases, the uterus will be turned inside out and forced out of the body.

The sad phenomenon of coffin birth occurs when the inside-out uterus is forced from the body while also containing a fetus. Outwardly, this may appear similar to childbirth, but the mechanisms behind it are totally different.

With regular birth, the body prepares by thinning and widening the cervix. In the case of coffin birth, the expulsion is the result of the decomposition.

The History of Coffin Birth

Postmortem fetal extrusion was first documented in a medical compendium published in 1896. The compendium, Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine, offered multiple examples of coffin birth dating back to 1551.

This first case was particularly ghastly. A woman who had been hanged had been observed to “give birth” to twins while still tied to the gallows.

Other examples of the postmortem fetal expulsion phenomenon are:

- Brussels, Belgium, 1633: A woman’s body expels a fetus 3 days after dying from seizure complications.

- Weissenfels, Germany, 1861: Sixty hours after death, a woman’s body is observed to have expelled a fetus.

- Hamburg Germany, 2005: A rare example of a postmortem fetal expulsion was observed when the body of a 34-year-old woman was found in her apartment after being dead for some time. She was 8 months pregnant, and when discovered, the head of the fetus was present outside of the vaginal canal. By the time the autopsy began, the entire head and the shoulders were visible. This was the first modern record of a coffin birth.

- Panama, 2008: A 38-year-old woman was found murdered four days after her disappearance. She had been 7 months pregnant at the time of the homicide, and upon examination the remains of the fetus were found in her underwear, still attached to the placenta which had not yet been expelled.

Coffin Birth in Archeology

With the extremely rare modern examples of coffin birth, the state of the remains often makes it easy to identify when the expulsion has occurred. This is much harder to do with remains that have been skeletonized, like the mother that we mentioned at the beginning of the article.

There are many examples of mothers being buried with their infant children. So the presence of fetal remains with the mother is not conclusive of a coffin birth. The much more likely scenario is that the deceased child was placed on the mother’s chest, in her arms, or beside her before burial.

A few cases of ancient coffin birth have been all but confirmed, though. Archaeologists look for the fetal remains to be lined up with the pelvic bones of the mother. This would indicate that the fetus was in the birth canal during or after the death of the mother.

The Mother in Imola, Italy

The body of the mother in Italy fits these qualifications and therefore is considered an example of coffin birth in archeology. Archeologists were also interested in the trepanation hole in the woman’s head. A hypothesis was formed that might explain both the trepanation and the coffin birth.

Trepanation was used to relieve symptoms occurring in the head, such as headaches, migraines, and other illnesses caused by intracranial pressure. One such disorder is called eclampsia, and it causes hypertension during pregnancy. This hypertension could have caused terrible physical pain, requiring doctors to perform the trepanation surgery to relieve the pressure on the woman’s head.

It is unlikely that the trepanation itself was the cause of death since there was evidence of some healing around the hole at the time of the skeleton’s discovery. Infection, or simply the eclampsia (which would have not been fixable via trepanation) might have killed the woman about a week later. This would have occurred while she was only two weeks away from reaching full-term in her pregnancy.

All of these variables combined may be a strangely perfect setup for a postmortem fetal expulsion. The remains of the fetus were found with the legs still positioned as if they were inside of the mother. This further cements the claim that her grave was an example of the extraordinarily rare phenomenon.

So while her death was tragic, and quite possibly agonizing for the poor woman at the time, her remains have enlightened scientists on not one, but two extraordinarily rare medical events.

References

“Rare Case of ‘Coffin Birth’ Seen in Medieval Grave”

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/rare-case-coffin-birth-seen-medieval-grave-180968612/

“Post mortem fetal extrusion: Analysis of a coffin birth case from an Early Medieval cemetery along the Via Francigena in Tuscany (Italy)”

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2352409X20302108

Note: For more details visit historydefined.net